Pollinator Pathmaker

An excerpt of the conversation between Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg and Sukie Smith.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg is a multidisciplinary artist examining our fraught relationships with nature and technology. Through artworks, writing, and curatorial projects, Daisy’s work explores subjects as diverse as artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, conservation, biodiversity, and evolution, as she investigates the human impulse to “better” the world. She experiments with simulation, representation, and the nonhuman perspective to question the contemporary fixation on innovation over conservation, despite the environmental crisis.

Sukie Smith has collaborated widely with directors, artists and musicians creating cross-disciplinary work, exhibiting and performing internationally. Having previously released three albums with her band Madam, Sukie has recently stepped out as a solo artist.

Full length conversation featured in Futuro Vol II.

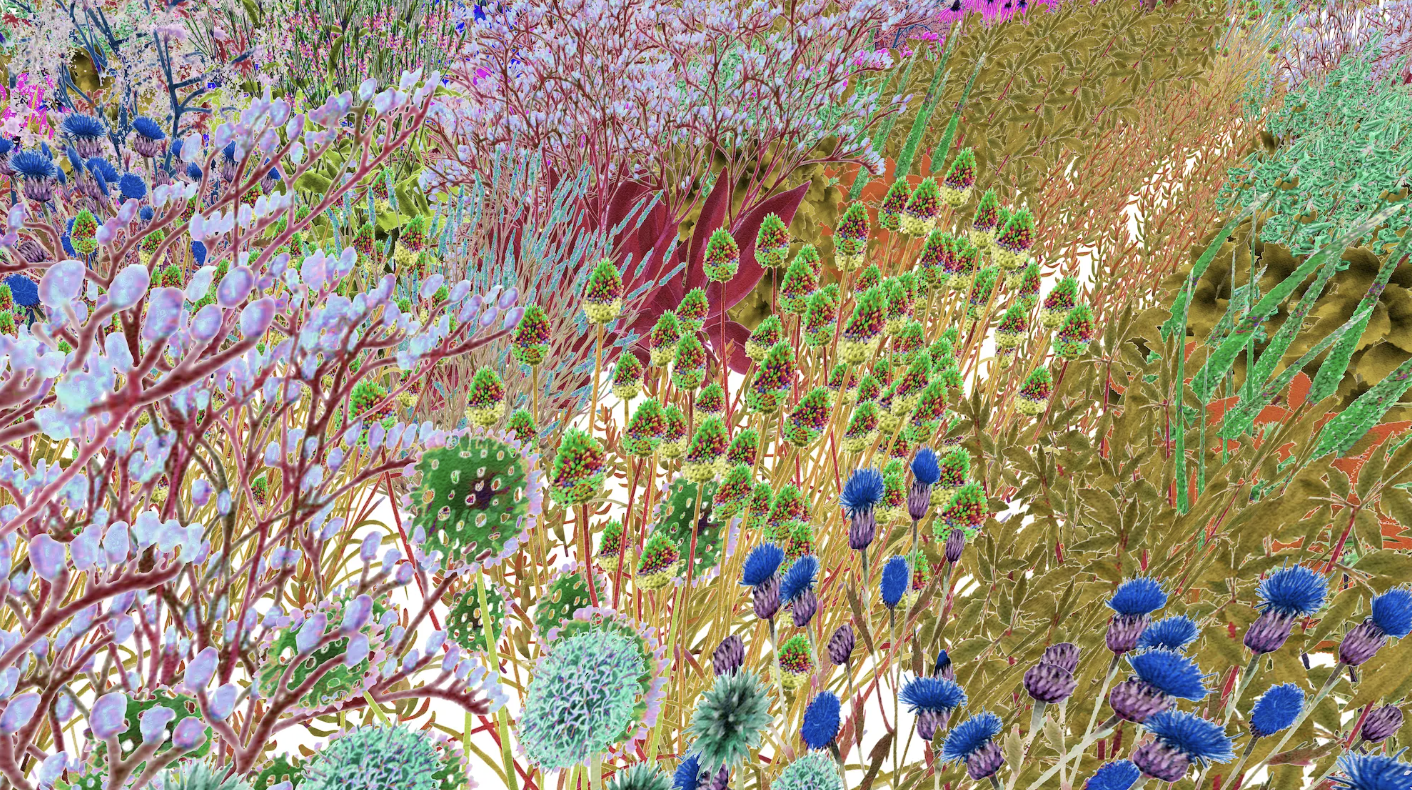

Pollinator Pathmaker, Digital render in pollinator vision, 2023. © Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg Ltd.

Sukie Smith Is the deliberate decision to have a different perspective, to think unlike a human, a starting point for you?

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg It is an impossible quest worth venturing into. How do we project the experience of another? Pollinator Pathmaker, in essence, was about how we can make something that takes us into the world of another but also shows the inadequacies of trying to imagine that other space. How can we open up that experience using art, to make us aware there is another world? That opens up lots of questions. Do insects even enjoy art? Do they have an aesthetic sense? Why do humans have an aesthetic sense?

Some of my other pieces, like The Substitute, and Resurrecting the Sublime, are using the framing of Western standards and modernity to reveal a different perspective. In The Substitute, I wanted to play with that moment where the animal (a digitally recreated northern white rhino) looks back at us. As it looks at you, that's totally anthropomorphic, we are projecting our feelings onto this rhino looking back on us, the rhino isn't there; it's a digital rendering that's being projected, but we want to feel that empathy, that connection. But, also, there's a sense of judgement from the rhino looking at us. But are rhinos judgmental? There is an effort to reveal the human lens rather than to get into the rhino's head. It's about the artificiality of recreating nature from the human perspective, and it's not nature if you do that. Pollinator Pathmaker is a little different because it tries to open up that reflection back on us.

Digital rendering of Pollinator Pathmaker Serpentine Edition in summer (detail). © Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg Ltd.

SS Do you have an agenda to make sure that humans understand their impact?

ADG I think the first step into empathy is the first step into treating our natural environment, which we are part of, better. So much of the problem with how we live is this conceptual separation of ourselves from the natural world that came out of the Enlightenment. We see nature as other to us. The point of modernity is to emancipate ourselves from the natural world and measure our emancipation. If we are thinking rationally, destroying our natural environment does not lead to progress because these things are intimately connected. But finding ways to reconnect is complicated with the narratives around the climate emergency and the biodiversity crisis, because it is just disaster. We feel paralysed; what can we do? Pollinator Pathmaker is an effort to give agency to individuals to participate in a group, to be able to do something. It won't solve the crisis, but it's the first step to action out of paralysis. Also, just looking at nature, tending to it and reconnecting with it is just a privilege for most of us in our everyday lives.

Cirsium rivulare 'Atropurpureum' flowers planted at Pollinator Pathmaker Serpentine Edition. Photo: Royston Hunt. © Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg Ltd.

SS Looking at the words you question that are in some ways so benign, like "progress" and "better," when did it occur to you that it was some kind of con?

ADG The short version is that I was on stage, and I realised I couldn't communicate to an audience full of techno utopians who wanted me to tell them I would make the world a better place. The longer version is that it comes from hanging out with synthetic biologists and the design community, all these different groups of people whose communities are focused on trying to improve the world. In design, there’s an embedded narrative that design makes things better, but it's bonkers. For example, this water jug has been designed to make it convenient for me to keep hydrated, and thus, my life is improved, but the jug has been designed as an individual object separated from everything around it. It's not, then, an icon of progress.

Digital renderings of the Eden Project Edition, in spring, summer, autumn, and winter (details). © Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg Ltd.

SS When did the function of design change?

ADG Design in itself as a profession came out of the Industrial Revolution, as a way of differentiating manufacturer A's plates for example from manufacturer B's plates. So, as a profession, it's very modern.

SS Is that the problem?

ADG Well how many plates do we need? We've been manipulated to want more plates. I think one of the big problems, and something that really interested me in my PhD, is that Gross Domestic Product is the measure of “better”. So growth is the measure, and what you measure is what you value, and what you value is what you measure. Since the 1940s, during World War 2 and post-WW2, that became the measure. So everything is about growth and everything good is measured through growth, but it doesn't consider human or environmental wellbeing because it's all about extraction. Design is a very human thing to do — to make a thing you have to extract a thing. One of the questions is: can design operate on other values that are not capitalistic growth values? And there are examples of that.

I don't mean to sound like a luddite, it's more about humans creating things for human benefit. But in modern Western society, we have forgotten that it's about the extraction of stuff to make stuff, to sell stuff, rather than what we actually need. That all gets very fluffy very quickly. The key message for me is that progress is a myth because how we measure progress is divorced from our natural environment. All the things that modern society has been built on for the last 500 years are disconnected from the natural environment. Without that element of progress, life expectancy, which has been going up, all these different measures have been improving, but they could all soon plateau and crash because of the environmental disaster.

Digital rendering of Pollinator Pathmaker LAS Edition in pollinator vision (detail). © Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg Ltd.

SS Listening to you speak about the concerns you address in your work, it strikes me that this is definitely female thinking. Very nurturing but equally warrior-like.

ADG Well, Alexandra means protector of men…

SS Exactly. And Daisy… Perfect. Sometimes when I am preparing to interview someone, a song will sing itself in my head, which perhaps resonates with the interviewee. I was listening to “Gimme Shelter” obsessively before I came to meet you. Are people looking to you to help them figure out how to survive?

ADG That would be too grand! Pollinator Pathmaker is asking people to join in and make their own editions and take ownership and continue to take care of the work beyond its connection with me. People plant their own DIY edition, which takes on its own life. There is a collaborative practice; it's a practice of land art but in a more feminist or eco-feminist way. That's how I'd like to see it because it is about care, nurture and collaboration. You have to also fight for a space to plant it. To have your own garden is a huge privilege, so you would then need to group together with other people to find a space — whether it's a school or a community space — and fundraise, and that is a step towards activism. Then you have to look after this thing together.

Pollinator Pathmaker, Digital rendering of Eden Project Edition (detail), 2021. © Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg Ltd.

CREATE YOUR OWN EMPATHETIC GARDEN ON

very laboratory